Beyond Crisis: A feminist humanitarian response that centers girls and young people

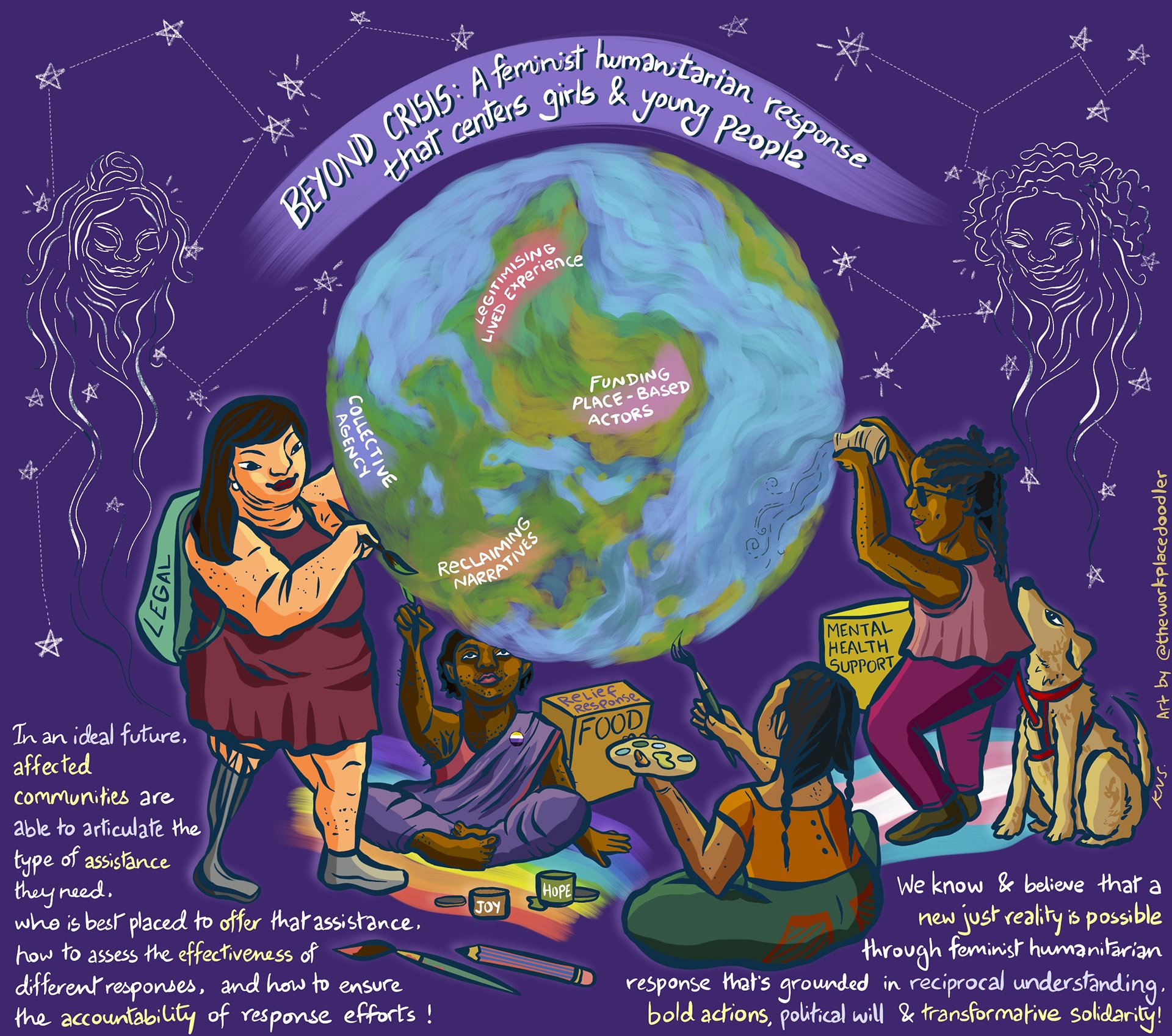

From Palestine to Ukraine, to Ethiopia, to Haiti, to Afghanistan, to Nicaragua - the world over - we are seeing increasing and intersecting crises fueled by oppressive and exploitative systems. With an ongoing global pandemic, wars and armed conflict, worsening climate crisis, the highest ever number of people in displacement, and rising inequality, humanitarian and chronic intersecting crises are only expected to worsen. Despite being disproportionately impacted by crisis, girls and young feminists continue to show up in consistent, brave and creative ways for their communities. Their work spans from providing direct services, supplies, food, access to legal resources and mental health support, all while holding the line and continuing their organising so that important gains in the feminist and human rights agenda are advanced.

Sometimes their activism is sparked as a result of a crisis, activated because of deep needs in their communities and the failure of governments or organizations to respond to these needs quickly, if at all. For others, responding to crises is a part of their long-term movement work and broader efforts to promote social justice. This is visible when we look at most emergency response efforts. For example, with Covid-19 relief, girl and young feminist activists responded to emergency needs in their communities while also amplifying and connecting vaccine access inequity as a core social injustice, which resulted in global attention and prioritization within the UN agenda.

Regardless of how they arrive, girls and young feminists are at the forefront of humanitarian response efforts during every crisis globally.

Girls and young feminists at the forefront of crisis response

In the absence of supplies and services, girls and young feminists develop mutual aid networks and solidarity economies to meet the urgent needs of their community members. They find channels- from analog to digital - to provide services and reach communities that the government and INGO’s do not, and they often play a critical role in providing mental health and wellness spaces.

In the context of Ukraine where the Global Resilience Fund has supported over 20 young feminist-led groups in the last few months, a recent activist dialogue showed that groups are continuing to provide frontline services, as well as support to people to flee the country and maintain movement connections, even as they are displaced across the region.

We are providing humanitarian aid in areas near the battle ground, based on solidarity networks. When we started, we didn't mark our boxes with feminist humanitarian aid. We created a form for individuals to access basic emergency health services, we tried to support individuals, our target audience was women in small villages and towns that the main humanitarian aid did not cover, and they are left without support. One day the driver who volunteered to deliver medication that we collected, said: “I thought all the feminist were doing something stupid before the war, and now I see that I was wrong”. That's how I know it is really important to represent myself as feminist. As for humanitarian aid It's sort of the black hole, but we try to make our contribution visible. - Anastasia, Feminist Lodge

In the context of Haiti, Nathalie from MARIJÀN | Feminist Organization reflects on their organisation’s response following the earthquake of August 14, 2021:

Our team went some months later to the scene because we were more interested in a post-earthquake intervention because often, after periods of crisis, we forget that these communities are left to themselves. In this sense, we accompanied more than 300 girls and women under the age of 25 for four months after the earthquake. Kits were distributed, workshops on sexual and reproductive health were conducted by our staff. We are proud of the work done in the south and the support given to the survivors.

Fatma from Feminist Initiative South Sudan shares about their work with their communities:

We offer psychosocial support for most marginalized women and girls, we meet twice every month and share different experiences, what we have gone throughout in our lives, as activists, and how we can overcome them, and have wellness and collective care sessions, and it makes sense to work on our mental health. We have outreach where we go to communities and we talk to marginalized women and girls and keep them updated as to what their rights are, including legal rights. In case of arrests, we also provide legal support and provide lawyers and follow up the cases.

During the Covid-19 pandemic girls and young feminists played critical roles in providing mental health services and support to their communities. Tiko from Helping Hand works in the conflict-affected and occupied parts of Georgia and shared a powerful account of the challenges their group is facing:

It is a really bad situation for young women and girls, as girls don’t go to school, don’t go outside, and there are high rates of violence and depression. We are seeing an increased number of suicides, with girls of 14 - 18 years old wanting to finish their lives. There is a stigma associated with seeking help. There is shame. To meet the needs of these girls, Helping Hand started providing mental health service support, hired professional psychologists and offered confidential space for people to talk and access support. Everything is done virtually due to the situation of the pandemic, and we are covering the internet costs of the girls, even using neighbors' houses and internet access.

Despite their critical efforts, girls and young feminists are under-resourced

Our experience in resourcing activists through the pandemic and in different humanitarian and emergency contexts has shown us that girls and young feminists continue to be underfunded and unrecognized for their response and organizing contributions during all crises. With around $30.9B in annual funding for humanitarian assistance, less than 5% is reaching women's rights organizations and, we suspect, an even smaller fraction for girl and youth-led emergency response work - failing to reach those at the forefront of and with the wisdom to support relief and just recoveries. This results in neglecting efforts led by communities, who are there long before a crisis hits, first responders to a crisis, and leading the recovery work - long after formal humanitarian response systems leave. Additionally, philanthropy and the humanitarian sector continue to respond to crises in scattered, siloed, and competitive ways that can perpetuate and exacerbate crises rather than resource and support the people at the forefront.

Tania from Nicaragua and Fatma from South Sudan share their experiences with the humanitarian system in their contexts:

I had to go into exile because there was a wave of persecution against artivists in Nicaragua by the Ortega dictatorship. And even though I have been supported by the humanitarian sector, I think that it is very inequitable and bureaucratic - creating obstacles for the most vulnerable people. It has to change these top-down ways of working as it is essential to support the people leading the social movements as they are the transforming agents of humanity. - Tania, Nicaragua

In South Sudan when it comes to the humanitarian context, for example UN agencies, it is very difficult for us to get funding, yes we have tried to apply many times, they will give us a reply of - ‘you do not have the capacity to handle those funds’. What do they mean when they say we don't have the capacity: they want us to have financial systems, which they have not helped us to build. We need that capacity building to help us do that. The money is not coming directly to us, we are a grassroots organization that reaches the community, we know what the community is facing, we know what the women and the girls are facing, because we are in direct contact and have relationships with them. Most of the time the funding is going to international organizations who do not have access to communities, they use studies and all this, but they do not have direct contact with them. So, in most cases, the support does not reach the community. - Fatma, South Sudan

There continue to be emergencies that grab the attention of the international funding community, such as we saw with Ukraine, while ignoring other crises such as in the Occupied Territories of Palestine, Lebanon, Somalia, Ethiopia, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Examples include the Swedish government that cut $1B from their aid budget to allocate it to Ukraine, and the United States government that welcomed 100,00 Ukrainian refugees when only a few months before told Central American asylum seekers to stay home. And in Ukraine where we were seeing large and unprecedented resources arriving, young feminists and feminist groups more broadly continue to be shut out of decision-making spaces, and the large majority of funding goes to more established International NGOs. We believe deeply in the response efforts to support those impacted by the war in Ukraine, and continue to fund powerful girls and young feminist response efforts in the region while advocating for all crises to be treated with the same urgency, level of resources, and grounded in the same respect and dignity for humanity.

From the experiences and lessons shared by girls and young feminists who are impacted by crises as well as others working on emergency response, we know that we must address the humanitarian industrial complex - the colonial, undemocratic, top-down, siloed, and centralized control of power and wealth in the humanitarian and philanthropic sector to maintain socio-political and economic leverage. As it results in unjust and inefficient solutions that further exacerbate humanitarian crises and do not address systemic injustices while limiting the accountability and role of specific governments, agencies, and businesses, especially by non-majority countries, that are fueling the very crises being addressed - one example of this is climate change.

As Sandie from Palestine reflects:

Despite some well intentions of many actors in the international aid sector, especially INGOs and UN agencies, their emergency work is still inherently imperialist, and they haven’t had a radical and practical stance to reform or dismantle the oppressive practices, hierarchies, and structures within which they operate. We have seen these institutions settle in our country, open fancy offices and many branches, assign their own global staff for senior management roles, hold the power of decision making and threaten local ownership in governance and leadership. These have been some of the key attitudes that communicated a message of patronship rather than partnership. The sector manifests on foundations of colonial legacy where the community of international aid is the “savior” and the “good doer”, reparations are off-topic, and the mainstream narrative is nothing short of capitalist and corporate exploitation in being and doing. We have always experienced transactional relationships with foreign aid community, and never has this relationship conveyed any messages of authentic solidarity.

Chernor also reflects on his experiences:

My view has been shaped by my frequent exposure to the patronizing relationships between aid donors and the countries and organizations they support. Too often, funding comes with narrow parameters, inflexible requirements, and problem-solving approaches that are like round peg solutions conjured up in Western capitals to fit in square holes.

Reimagining humanitarian response through a feminist lens

If our goal is to truly provide humanitarian relief, we must also address the core issues that are creating humanitarian crises in the first place. This will require dismantling the humanitarian industrial complex through a feminist humanitarian response. What does this mean? As explained in the report Toward a Feminist Placed Based Response to Forced Displacement: “In an ideal future, affected communities are able to articulate the type of assistance they need, who is best placed to offer that assistance, how to assess the effectiveness of different responses, and how to ensure the accountability of response efforts.”

An intersectional feminist approach requires us to go beyond a single-issue focus and short-term needs to focus on the root causes of humanitarian crises that are deeply connected to systemic injustices. Only then can we understand, respond, and contribute to a world that eradicates the systems that continue to fuel crises in the first place. This requires us to resource resistance, and support the urgent relief, long-term strategies, and care to sustain the people powering grassroot efforts and movements.

Echoing Sandie’s words:

We know and believe that a new just reality is possible through feminist humanitarian response that is grounded in reciprocal understanding, bold actions, political will, and transformative solidarity. Moving away from centralization, condescension, the white gaze and supremacy, and transactional neo-liberal funding, a new world is by default in the making and the needs of marginalized communities and victims of conflicts are at the heart and center of resource distribution and power collectivizing.

It also requires us to ground in feminist principles of solidarity and trust to move girls and young feminists the kinds of resources they need to do to this critical response work. Through the work of the Global Resilience Fund, we have seen it is possible to move flexible resources at speed, while also working with young feminists from relevant contexts to guide the process and make funding decisions. Similarly, we have been able to adapt and meet girls and young people where they are, supporting unregistered groups, using paypal, paying cash or by working with fiscal sponsors. Every funder can work towards processes that are more accessible, flexible, inclusive, and participatory. The experiences of funders shifting their practice to be in deeper solidarity with communities and to be truly flexible is highly relevant to reimagining funding in humanitarian contexts, and we continue to see new ways to provide better funding.

Taking an ecosystem approach to better understand how different actors across the humanitarian system - from government, to UN agencies, to private and public philanthropy to movement and communities - can work together to build on each other's strengths - while holding the reality of varied power dynamics and a need to unlearn and reimagine concepts of risk, and decolonise aid and ourselves. If the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have taught us anything - it is that our fates are inextricably intertwined and our mutuality is essential to survive and thrive.

As crises continue to deepen inequalities and injustices, we cannot continue to fail by not reaching those at the frontlines of emergency response: girl and young feminist activists. Their work is essential in crisis and as we work toward addressing the systemic issues that perpetuate crises. Investing in a feminist humanitarian response that centers girls and young feminists activists will lead us beyond crisis response to sustained social transformation and our collective liberation.

GRATITUDE

This piece was illustrated by Kruthika NS, lawyer and social justice artist @theworkplaceDoodler, and inspired by reflections and conversations with girl and youth activists with lived experiences and at the forefront of crisis response and organizations working on transforming the humanitarian sector such as the Feminist Humanitarian Network.

ABOUT US

Anatasia Chebotaryova is a young feminist activist from Ukraine and is part of Feminist Lodge - a grass-roots informal initiative called of young intersectional feminist activists. They are focused on developing an intersectional and left-willing feminist agenda in Ukraine through lectures, film screenings, art projects, And currently volunteer for women and girls and other vulnerable groups affected by war. They were created in October 2017.

Chernor Bah is a feminist activist who has dedicated his life to building the power and amplifying the voices of girls and young people across the globe and in his beloved Sierra Leone. At the age of just 15, Chernor founded and led the Children’s Forum Network, a mass movement of children who organized and mobilized to demand their voices be included in peace and reconciliation efforts after Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war. When Ebola struck Sierra Leone, Chernor co-launched Purposeful to support the emergency response and long-term recovery in his beloved home.

Tingiba Fatma Iddi is a feminist, key population rights activist and a human rights defender. Fatma is a community paralegal and a champion against gender based violence. Fatma is the founder and the national coordinator of Feminists Initiative South Sudan (FEMISS) a feminist and Key population led Organization in South Sudan.

Jody Myrum has a lifelong commitment to the dignity, safety and freedom of all girls and young people. Grounded in social work and a deep commitment to racial, gender and youth justice, Jody is a feminist activist, strategist, and centers lived experience in research and storytelling to transform narratives. She works across movements, organizations and philanthropy to center girls and young feminists and to move resources and power to those working to build their collective power.

Laura Vergara is a cuir (queer) Colombian feminist activist sprouting collective action through the power of storytelling. Impacted by continuous generational displacement in Colombia due to systemic injustices and violence, her activism began over a decade ago through her work within the immigrant and refugee rights movement and expanded across feminist and intersecting social movements. She finds inspiration in social movements, collective care, art, and those that root themselves in solidarity and love.

Ruby Johnson is a feminist organiser, strategist and researcher, committed to redistributing resources and power to girls young feminist movements. Ruby has experience advancing gender justice and human rights with grassroots groups, feminist organisations, womens’ funds, foundations, NGOs, and UN agencies with a focus on women, girls, trans and non binary people. She collaborates with organizations to build strategies and funding approaches and design programs in participatory and creative ways. She works to build bridges and deepen accountability between movements and philanthropy and has a passion for collaborating with artists and storytellers to build narrative power.

Nathalie E. Vilgrain is a feminist activist with a degree in political science and feminist studies from the University of Ottawa. She is passionate about the situation of women and girls in the world and has worked in Haiti and in Canada with women survivors of violence. Her areas of interest are many such as gender equality, survivor safety, participation in politics, sex workers' rights, LGBTQI2+ rights and women's reproductive and sexual health. She is a founding member and the first co-coordinator of MARIJÀN a feminist organization in Haiti. As a Caribbean feminist and women's rights advocate, her work focuses on advocating for social justice through activism and capacity building of local organizations.

Sandie Hanna is a feminist, human rights and anti-imperialist activist from occupied Palestine. She is the founder of Feminist Diaries, an intergenerational collective of young women and girls who analyze and produce art to share stories about their lived realities under settler-colonialism and patriarchy, activism journeys and the feminist world they dream to co-shape. She is the Arab States Program Officer of With and For Girls Fund, the world’s first Africa rooted global fund for girl activists and their allies.

Tania Molina is a Nicaraguan artist and feminist activist, currently a political refugee in Costa Rica due to threats from the Ortega dictatorship in Nicaragua. She has been the founder of a network of artists and works with feminist networks that use art as a central part of activism. She has performed in local and global feminist politicized spaces and raises awareness about the dictatorship in Nicaragua.

Tiko Meshi is a young feminist activist from Georgia who formed Helping Hand. Helping Hand is a women-run NGO with a mission of inspiring and equipping youth as volunteers to meet the needs of their communities. Vision is of a world where united and engaged youth (ages 14-31) discover their power to create a change and are supported by an extended network of over 1000 volunteers. Through volunteering they strive to support young women and girls, non-conforming youth, people with disabilities, most vulnerable families challenged by poverty, homeless youth and children. They also serve girls affected by the Russian war and living in conflict-affected regions of Georgia.